An Afternoon with Michaela Carter

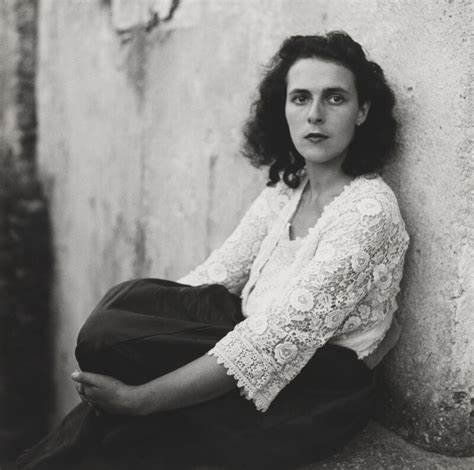

Author and poet Michaela Carter has captivated readers with her novel Leonora in the Morning Light, which delves into the life and historical significance of artist Leonora Carrington. With three of Carrington’s works in our permanent collection, we sat down with Carter to gain a deeper understanding of the story through the author’s perspective.

“There’s her androgyny, her strangeness, her fierceness and her confidence that comes through in all of her work. Also, there’s a playful quality. Clearly, she was having fun. She wasn’t trying to please anyone but herself. She didn’t care if anyone understood her pieces. She supported herself with her art, but she also made art for the sheer sake of making art. She couldn’t help herself. I think we’re finally beginning to catch up to her. I see her being a beacon for generations to come.”

If there’s one thing wordsmith Michaela Carter wants you to know, it’s that Leonora Carrington was far more than any man’s muse.

The Carrington we meet in Carter’s novel, Leonora in the Morning Light, is enigmatic, beautifully intense, and carries a sharp sense of humor that endures—a beacon of hope that inspires both authenticity and resilience. Overall, Carrington is the ideal figure for the present moment, which may explain why she is undergoing a re-evaluation as one of the most significant artists of the Surrealist Movement.

In our interview, Carter graciously agreed to answer some of our burning questions about Carrington and her experience writing the novel. From the challenges of capturing the complexities of a historical figure to the shifting public perception of Carrington as her legacy gains more attention, our conversation delves into what happens when society finally begins to recognize the genius of this extraordinary artist.

OF - Why Carrington? What captured your attention or imagination? Was it her work, personhood, or a mixture of the two?

MC - When I was at the Tate Modern in London I saw one of her pieces in a surrealism exhibit of mostly male artists, and I was taken with the strangeness and urgency of it, as well as a quality I can only describe as masterful, utterly confident, as if she wasn’t looking outside of herself for any sort of approval or reinforcement. I was also amazed that I hadn’t heard of her.

Then I read the book Susan Aberth wrote about her life and work and I felt a quickening. I knew that the story of her early life—falling in love with Max Ernst, running from the Nazis, being sent to a Spanish asylum by her father and the transformation she underwent in the process would be my next book, if I dared to write it.

OF - After both researching and writing, do you feel a kinship with Carrington? Do you have any internal parallels in your shared experiences as writers, painters, and, of course, women?

MC - I am in awe of Carrington. She produced over 5000 works in her lifetime and she very much lived her own life, at a time when it was even more difficult for a woman to do so. She’s become, for me, a kind of artistic guardian angel, inspiring me to trust myself, to move faster than I think I can, and to stretch the boundaries of who I think I am and what I believe I can do.

OF - Upon setting out to write this novel, did your direction or intention ever shift along the process? Were there any particular moments in the writing process where you felt your perception of Carrington or the narrative itself evolved?

MC - Absolutely! When I realized just how large a role Peggy Guggenheim played in the story of Max and Leonora I was, at first, disheartened. I was halfway into the novel and thought I could wrap up the tale in 300 pages or so, and that the book was about two people rather than three. But then I fell in love with Peggy and her humanness, her insecurities. And I realized that the story needed her in it. She played a key role in bringing Modern Art from Europe to the US. She was the first collector to buy a Carrington and she got Max out of the reach of the Nazis and to New York City.

OF - Your prose in Leonora in the Morning Light has been referred to as very lyrical and rhythmic. Did your background in poetry influence your long-form writing style?

MC - I’m sure it did. I love lyrical writing. Writing and reading poetry helped me realize the importance of the sentence. For me, the rhythm of a novel I’m reading carries me through it as much as the story does, and that’s the case when I write as well. I read my work aloud as I revise and if the rhythm feels clunky, I rework that section until it flows.

OF - Was any of your writing style influenced by Carrington’s short stories or books? Were there any specific stylistic elements or themes in Carrington’s writing that you sought to emulate or contrast in your own work?

MC - Reading her short stories and her wonderful novel The Hearing Trumpet, I was struck by the strangeness of them—especially her stories. My novel includes a few very short stories I wrote as if she had written them. In these, I consciously opened myself as a channel for her energy. This was after years of immersing myself in her life and her work and the stories came easily. It was thrilling being in her world.

OF - What has been one of your favorite anecdotes about or from Carrington? Any particular quotes that continue to resonate with you?

MC - One of my favorite anecdotes is when she cut locks of her guests hair while they slept and then cooked the hair into individual omelets which she served them. I had to put it in my novel, which meant I needed to know how hair smelled when you sautéed it and what it was like to eat it. So I cut some of my own hair, fried it up and tried it. I think at this point my husband started to worry I was going overboard!

As for powerful quotes, she has many, but the two that have continued to inspire me come from a commentary she wrote for her 1976 retrospective in New York City. “A woman should not have to demand Rights. The Rights were there from the beginning; they must be taken back again.” And, in closing, “Footprints are face to face with the firmament.”

These two quotes give me strength. They also speak to the fact that women’s rights go hand in hand with the rights of nature. Carrington considered herself an ecofeminist. She fought for women’s rights in Mexico and spoke out against the destruction of the Earth.

OF - What does it feel like to be among the first to help promote Carrington’s legacy in the literary world?

MC - I feel extremely lucky—to have encountered her when I did and to have believed in myself enough to write a novel about her. As I was writing the book, I felt an urgency to get the work out, but I also knew it had to be right. Once something is published it’s out of your hands, and I didn’t want to rush it. I wanted it to be as strong a work as possible and worthy of her.

OF - Historically, Carrington has often been reduced to being seen as Max Ernst’s muse, despite her own rejection of that label. As her recognition grows, do you think it could open the door for more women artists—particularly those who have been overshadowed by their male counterparts—to gain the attention they deserve?

MC - Absolutely! So many women are being “discovered” in those shadows. I’m amazed by how many incredible painters and writers I never knew about because they were with famous men who, until now, have garnered all of the attention.

OF - As a follow-up, how do you think your book contributes to the “mythos” of Carrington? What aspects of her iconography do you believe are relevant to the current moment?

MC - You know those faces with rays coming out of them which so often appear on the chests, or hearts, of her creatures? To me, they signify courage and the willingness to risk feeling rather than staying safely ensconced in thinking. The culture has been so completely dominated by men that thinking has overshadowed feeling, but the heart possesses a power the mind doesn’t, and she knew that.

There’s an androgyny to many of her creatures that feels perfect for this moment. It took us a while to catch up to her, but we are finally embracing the male and female aspects in all of us, regardless of sex and gender.

And then, there are her horses! She felt a kinship with horses since she was a child. When I look at her first paintings, which feature horses, I feel their agency, power, and freedom. We need that more than ever now.

OF - Why do you think Carrington is having such a significant cultural moment? It’s been over a decade since her death, yet suddenly it feels like she is everywhere. What do you think is drawing audiences to Carrington now, and why do you think her work resonates particularly with contemporary readers and artists?

MC - There’s her androgyny, her strangeness, her fierceness and her confidence that comes through in all of her work. Also, there’s a playful quality. Clearly, she was having fun. She wasn’t trying to please anyone but herself. She didn’t care if anyone understood her pieces. She supported herself with her art, but she also made art for the sheer sake of making art. She couldn’t help herself. I think we’re finally beginning to catch up to her. I see her being a beacon for generations to come.

OF - Mental health plays a significant role in Carrington’s life story, and it often shapes her public perception. While society tends to glamourize the quote tortured artist quote—especially when they die young—Carrington lived on, continuing to create after being kidnapped and institutionalized. What do you think her resilience in the face of such hardship says about the strength of the human spirit?

MC - I see her time in the asylum as being a furnace for her development as an artist and for her individuation. After that intense hardship and her harrowing escape, she knew if she was going to expand creatively and spiritually, she needed at the same time to ground herself so as not to lose herself in the ether. She needed to plant her feet on earth in order to function as a sort of lightning rod for inspiration.

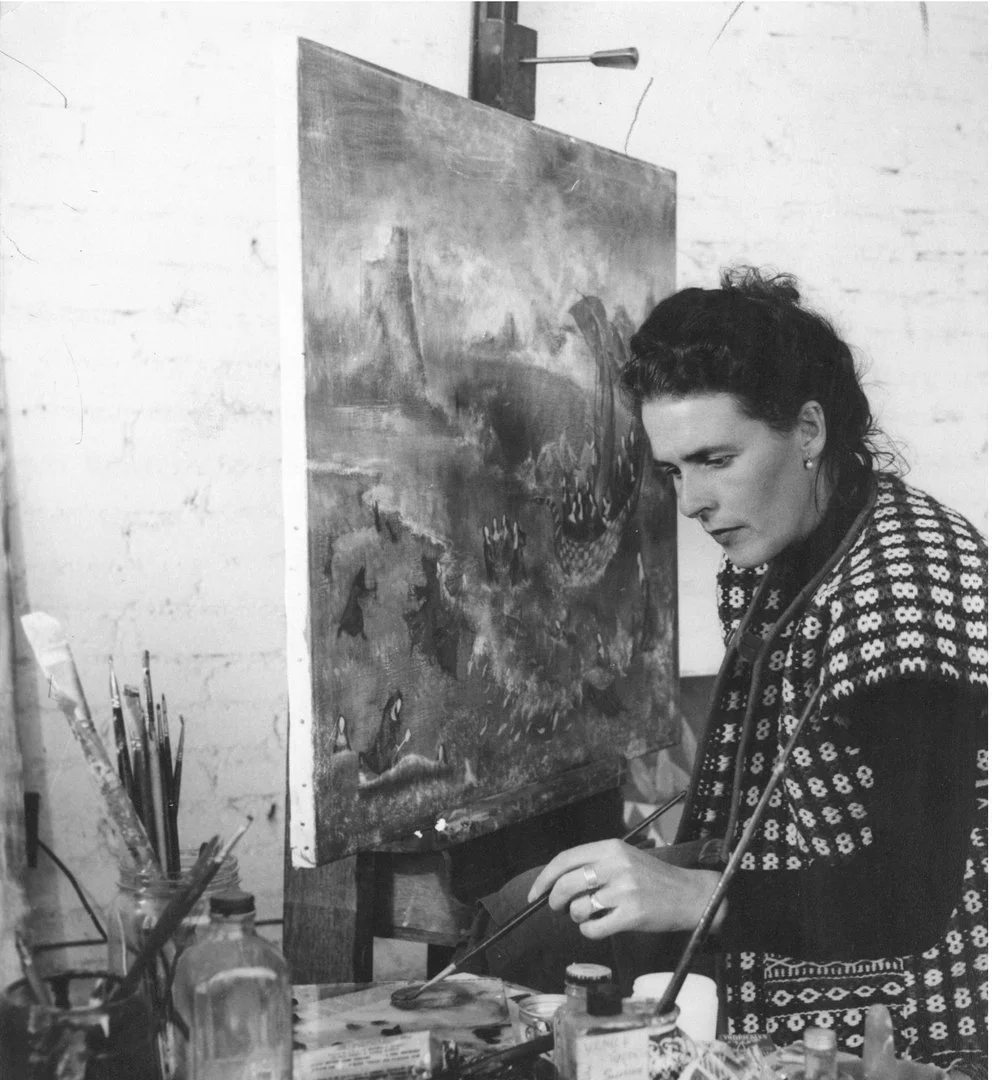

“Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse)” (1938).

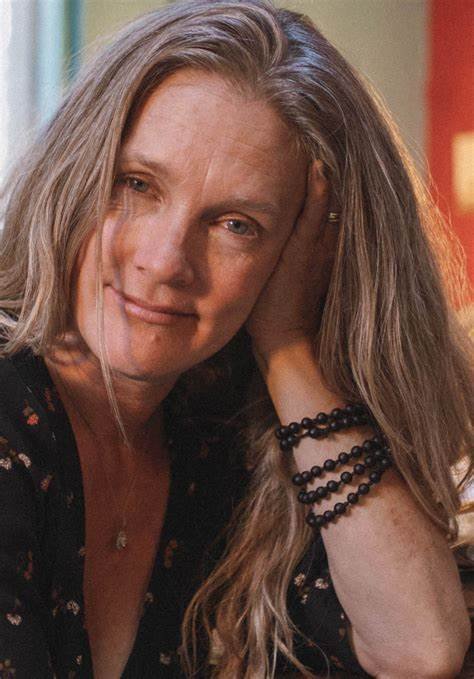

Experience Leonora in the Morning Light for yourself!

Support Michaela Carter’s independent bookstore, Peregrine Book Company in Prescott, Arizona, by ordering directly from them below. You can also explore reviews and discover more about the novel through the second link.

Plus, don’t forget to check out the audiobook on Audible and Spotify.